Quetzalcoatl Prophesies & Spanish Christian Conquest

The following paper was written in 2013 and presented at a history conference in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

The following paper was written in 2013 and presented at a history conference in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

When the Spanish Conquistadors marched into the Aztec capital city of Tenochtitlan they learned from the native emperor Montezuma himself that they had been expected. In the words of Bernal Diaz, a firsthand witness, the monarch informed the newcomers that they "must truly be the men about whom his ancestors had long ago prophesied, saying that they would come from the direction of the sunrise to rule over these lands." [1] Surprisingly, Montezuma seemed almost eager for the Spanish emperor Charles to displace him as the ruler of Mesoamerica, and he expressed his willingness to fulfill his ancestors' prophesies. [1] The Aztec ruler quickly told his lords and vassals to submit to the Spanish authority and pay tribute without resistance. [1]

Throughout Bernal Diaz's account of the Spanish conquest of Mesoamerica, the natives viewed the Spanish as prophesied gods long foretold. The Conquistador's Yucatan allies the Tlascalans told the Conquistadors that their gods prophesied their coming, [1] and the Spanish were referred to as "Teules" by the Mesoamericans. The word means "gods" or "devils."

References to fulfilled prophesy are so common throughout firsthand accounts of the conquest story that it seems impossible to dismiss them as inaccurate. The prophesies play such a large part in explaining Montezuma's behavior that removing them from the narratives would render the conquest events almost unintelligible.

It is increasingly popular for students of the Mesoamerican conquest to claim prophesy stories were invented in post-conquest scenarios by Europeans eager to justify their invasion. Can this modern analysis survive scholarly criticism? It turns out that the majority of evidence leans in favor of pre-contact origins for most of the prophesies.

Although a small minority of scholars like Camilla Townsend of Rutgers University has speculated that the Indians did not really believe the Spanish were gods, even she has admitted they at least saw the Conquistadors as bizarre sorcerers sent from a higher power. [2]

Christopher Columbus believed the natives thought the Europeans were heavenly beings when he commented on their trading habits in a March 14, 1493 letter:

"Their liberality in dealing did not proceed from their putting any great value on the things themselves which they received from our people in return, but because they valued them as belonging to the Christians, whom they believed certainly to have come down from heaven, and they therefore earnestly desired to have something from them as a memorial." [3]

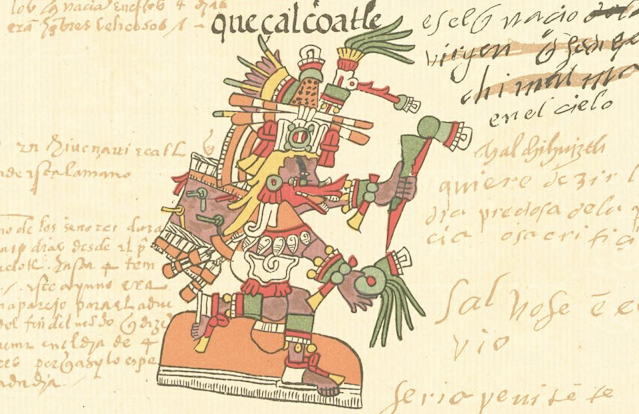

Bernardino de Sahagun, the great sixteenth century historian of New Spain, recorded that emperor Montezuma thought that Cortez "was Topilzin Quetzalcoatl who had arrived." [4] Topilzin Quetzalcoatl was an ancient Toltec god who had sailed into the East promising to eventually return.

Eyewitness Conquistador Bernal Diaz recorded many encounters with prophesy throughout his chronicle of the conquest. His record of the events is especially believable because he personally repudiated some of the more exaggerated claims of divine intervention during the campaign. He volunteered, for example, that he never witnessed saints fighting on behalf of the Conquistadors as some of his peers claimed.

The sixteenth century historian Friar Diego de Landa, who worked among the post-conquest natives, wrote that just "as the Mexican people had signs and prophesies of the coming of the Spaniards and the end of their power and religion, so also did those of Yucatan some years before they were conquered." [8]

Lord Acton, of "absolute power corrupts absolutely" fame, commented in his Cambridge Modern History that "the coast tribes mistook… [Cortez] for the ancient Toltec god Quetzalcohuatl." [9] British writer Maurice Collins commented in his book 'Cortez and Montezuma' that "when Cortez anchored off the mainland on the eve of Good Friday… he had no idea that he was a god in mortal form whose second coming had been foretold for the morrow." [10] The Encyclopedia of World Biographies says that Montezuma feared that Cortez and his men were "emissaries of the Aztec god Quetzalcoatl, whose return they believed to be imminent." [11]

In the middle of the twentieth century, historian Miguel León-Portilla sought to tell the story of the conquest of Mexico through the words of the Aztecs themselves. After compiling the 'The Broken Spears: The Aztec Account of the Conquest of Mexico,' he wrote that Montezuma went out to meet the Spanish as they entered his capital "in the belief that the white men must be Quetzalcoatl and other gods, returning at last from across the waters." [12]

One of the most prestigious Mesoamerican historians of our time, Harvard Divinity professor David Corrasco, commented that "a review of the primary sources reveals that this ancient priest king [Quetzalcoatl] was born in the year 'ce acatl'… and was expected to return in the year 'ce acatl.' It is one of the amazing coincidences of history that the Aztec year 'ce acatl' fell on the Christian year 1519, the year that Cortes appeared in Mexico." [5]

If these prophesies existed as part of the tradition of pre-Columbian Mesoamerican civilizations, then what exactly where they predicting? As we have already seen, many scholars have claimed that a large part of the prophesies related to the return of the Toltec god Quetzalcoatl in the year "ce acatl" (which happened to correlate with AD 1519). [7]

It is revealed in Friar De Landa's book that the natives recorded a tale of a priest who prophesied their coming future:

"an Indian named Ah-cambal, filling the office of 'Chilan,' that is one who has charge of giving out the responses of the demon, told publically that they would soon be ruled by a foreign race who would preach a God and the virtue of a wood which in their tongue he called 'vahom-che,' meaning tree lifted up, of great power against the demons." [8]

This account indicates that the pre-Columbian Mesoamericans prophesied that the coming of the Spanish would bring foreign domination from a strange race, and the advent of a new religion vastly different from the one they had known. The "vahom-che" ("tree lifted up") is an interesting subject we will revisit later.

De Londa's book also reveals another prophesy recounted to him by a very learned native who produced a book belonging to his grandfather showing pictures of large deer. De Landa wrote: "his grandfather had told him that when there should come into the land large deer (for so they called the cows), the worship of the gods would cease; and this had been fulfilled, because the Spaniards brought along large cows." [8]

In other sources, it is clearly stated that the emperors of the Aztec Empire were only seen as place holders for the great Quetzalcoatl and would subsequently relinquish the throne upon his return. This was apparent when Montezuma spoke to Cortez upon arrival:

"O our lord, thou has suffered fatigue; thou hast spent thyself, Thou has arrived on earth; thou has come to thy noble city of Mexico. Thou hast come to occupy thy noble mat and seat, which for a little time I have guarded and watched for thee… Lo, I have been troubled for a long time. I have gazed into the unknown whence thou hast come - the place of mystery. For the rulers (of old) have gone, saying that thou wouldst come to instruct the city (that) thou wouldst descend to thy mat and seat; that wouldst returned. And now it is fulfilled: thou hast returned…" [4]Corrasco explained it:

"The sources tell us that while Mexico-Tenochtitlan 'remained,' it's kings and priests and nobles awaited the return of a royal ancestry whose coming might 'shake the foundations of heaven' and who would conquer the city. It was to Tenochtitlan, the 'alter' of Mexico… that Quetzalcoatl was to return one day and reestablish the kingdom he had abandoned centuries before." [5]

Some sources appear to indicate that Quetzalcoatl was expected to send his sons back before him to extract revenge upon the people who had driven him out. Father Diego Duran, a sixteenth century priest working with the Indians in New Spain, believed that because the natives had driven Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl from his domain in the city state of Turan that God had sent the Spanish to take the land from its Indian usurpers as punishment. [13]

What makes the Quetzalcoatl prophesies so eerie is that they extend beyond a simple foretelling of the future Conquest events into seemingly banal descriptions of Quetzalcoatl that appear to describe Cortez and his men. According to a transcript of an ancient oral tradition taken down in the 1500s, Quetzalcoatl was a heavily bearded man possessing a bizarre looking face: "His face was like something monstrous, battered… and his beard was very long, very lengthy." [7] [12] This is a startling description considering that most Native American men cannot grow facial hair (especially not long thick beards). [14] However, European men generally can grow beards, and Cortez and his men were bearded.

Another interesting comparison in appearances emerged when Montezuma requested to see Cortez' helmet. After comparing the helmet to those worn by his gods, Montezuma was convinced Cortez was of the race his ancestors prophesied would come and rule the land. [1] The story was recounted by the eyewitness Bernal Diaz. It seems unlikely Diaz would have fabricated such a strange and seemingly insignificant story.

There can be little doubt the Mesoamerican prophesies regarding the return of Quetzalcoatl originated in the pre-conquest era. Sahagun composed a document called the "Florentine Text" which prominent Aztec historian HB Nicolson claimed was "one of the most remarkable accounts of a non-Western culture ever composed." Sahagun certainly believed the prophesies were an authentic part of Aztec religious belief.

It has also been found that the pre-Columbian peoples of the Caribbean, Paraguay, Brazil, and the Northwest United States all shared similar stories about people coming from the East to conquer them. [1]

If we are going to accept that these very specific prophesies were pre-conquest in origin then we should probably begin asking the challenging questions related to that acceptance. Where did these prophesies come from? What did they originally mean to the natives? Was their fulfillment during the Spanish conquest just a strange coincidence?

There are numerous theories. A quick scan of the internet reveals many competing ideas. Perhaps the prophet Quetzalcoatl was a Viking. [15] Perhaps he was from an early Chinese voyage. Or, perhaps, Quetzalcoatl really was a priest king gifted with prophesy. Many early thinkers thought he was the Apostle Thomas who allegedly traveled beyond India. [16] Many Mormon scholars have claimed that Quetzalcoatl was Jesus Christ himself. [17] Is there any evidence that might lead us to a conclusion about these prophesies and the enigmatic priest king at their center?

Is it possible that an early Christian missionary or European traveler made it to the New World and taught a new religion in Mesoamerica? Surprisingly, this theory is less farfetched than one might imagine. In fact, the Florentine Codex records some of the historical teachings of Quetzalcoatl. The teachings associated with Quetzalcoatl's city state endorsed strict monotheism and referred to a God simultaneously in heaven and on earth in human form:

"Only one was their god… they prayed to one by the name of Quetzalcoatl. The name of one who was their minister, their priest was also Quetzalcoatl. That which the priest of Quetzalcoatl required of them they did well… he admonished them. 'There is only one god; [he is] Quetzalcoatl.'" [4]It appears unlikely that in the middle of a militaristically polytheistic society there emerged a solitary figure preaching a strong insistent monotheism, and that this monotheism bore so much in common with the Christian incarnation. Harvard Professor David Carrasco has commented on how Quetzalcoatl was seen as an incarnation of another Quetzalcoatl in heaven, and that his life was imitated as Christ's life is imitated by Christians:

"Quetzalcoatl… the earthly priest who is the incarnation of the deity Quetzalcoatl… Quetzalcoatl as man and god together was the living center of the image of Tollan [the city state he ruled over]. That this interpretation reflects the indigenous understanding is reflected in the summarizing statement: 'Quetzalcoatl became the pattern for the life of every priest.'" [5]The Christian concept of the high priesthood of Christ was imitated in the image of Quetzalcoatl. As 'Broken Spears' editor Miguel Leon-Portilla observed:

"[Quetzalcoatl] was also invoked as the… 'Precious-Feathered-Twins,' at once the name of the god and of his priest." [12]

Another interesting similarity is that followers of Quetzalcoatl took his name as a marker just as Christians have taken Christ's name. The ancient tradition says: "And one who had distinguished his way of life and otherwise had followed the precepts… They gave him the name of Quetzalcoatl."

When selecting a new high priest of Quetzalcoatl the tradition says:

"Not lineage was considered, only a good life. This indeed was considered. Indeed this one was sought out, one of good life, one of righteous way, of pure heart, of good heart, of compassionate heart, one who was resigned, one who was firm, one who was tranquil, one who was not vindictive… one who made much of others, one who embraced others, one who esteemed others, one who was compassionate of others, one who wept for others, one who sorrowed." [12]

There are similarities between these qualifications for Quetzalcoatl's priests and the beatitudes of Matthew 5. The list represents a startling contrast to the religious practices carried out in honor of the other gods including the brutal practice of human sacrifice and cannibalism which was so prevalent throughout the pre-Columbian world, and it is interesting that Quetzalcoatl himself condemned this practice and never participated in it. This is the likely reaction of any Christians who would have come into contact with such horrible barbarism. [7]

The religion surrounding Quetzalcoatl also resembled the Christian tradition in the Mayan world creation mythology. The great creation myth in the 'Popol Vah' of the Mayan people reads:

"Whatever there is that might be is simply not there: only the pooled water, only the calm sea… So there were three of them, as Heart of Sky, who came to the Sovereign Plumed Serpent [Quetzalcoatl], when the dawn of life was conceived… 'But there will be no high days or no bright praise for our work, our design, until the rise of the human work, the human design,' they said. And then the earth rose because of them; it was simply their word that brought it forth. For the forming of the earth, they said 'earth.'" [6]

In this Maya genesis myth we find a triune godhead, including the "Jesus figure" Quetzalcoatl, discussing their future creation of man over a water world. Their voice alone brings the world into existence. This mythology appears astonishingly similar to the creation account of biblical Genesis. This seemingly biblical version of the story cannot be dismissed as a post-conquest manipulation because it was discovered on an eighth century AD Mayan stela belonging to the king Kawak-Sky. [6]

Perhaps even more perplexing are the "World Tree" images used by the Mayan as their axis mundi. These World Trees were shaped and presented precisely as the Christian cross. In fact, the name of the tree, 'Wakah-Chan,' is literally interpreted "raised up." This seems to parallel Christ's words about being "raised up" to draw all men to himself. The tree was also treated as a living creature directly associated with the "First Father" figure who possessed a human form in addition to also being the World Tree. First Father was sacrificed to the gods of death resulting in the rebirth that gave rise to man. [6] These traditions arose during the Mesoamerican classical era long before the influence of European Conquistadors. [6]

Through the myth of First Father, the World Tree cross is directly tied to a myth very similar to the story of Christ being sacrificed to the death god Satan to ransom the human race. Quetzalcoatl was said to have died and descended to hell where he anointed the bones of the dead with his own blood and gave birth to a new race of human beings. This sounds similar to Christ giving rise to a new Christian race after his death burial and resurrection. [7] [18]

Besides the Christian elements which seem to appear in Mesoamerican religion, there are also records suggesting Quetzalcoatl introduced other innovations into pre-Columbian society. Among these were books and calendars. [7] Could it be that an early Christian missionary introduced various technologies and learning into Mesoamerican culture?

Finally, it is important to consider whether or not Quetzalcoatl was a historical figure. We must first know if he actually existed before we can hope to answer any questions about his origin. Carrasco addressed this problem when he wrote:

"Since the initial gathering of information about Aztec Mexico, a constant and heated debate has focused on the identify of Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl, [and] the location of his city… the present consensus has 'proven' that this hero was a historical individual." [5]

Is it possible the Aztec and Yucatan people mistook Cortez for Quetzalcoatl because he physically and religiously resembled the ancient priest king of the Toltec era? Perhaps Cortez and the arriving Spanish resembled the ancient god because they both originated from a similar ethnic and cultural civilization. Could this be the reason the prophesies of the Mesoamericans appear to be so accurate in their descriptions of the coming messiah?

Is there any better explanation for the ancient prophet's ability to foresee the bearded armored men arriving from across the Eastern Sea to demolish their idols, establish monotheism, and banish human sacrifice? Is there a better explanation for why they wrote biblical sounding creation myths, a living cross axis mundi, an incarnational death and resurrection story, strict monotheism, and a priesthood based on radically different ethics?

Perhaps it is time to reevaluate old claims by past historians about the Christian origins of Mesoamerican mythology.

NOTES

[1] Diaz. 'The Conquest of New Spain,' Cohen, J.M. Penguin Books, England. 1963. Pages: 210, 271, 264, 308.

[2] Townsend. 'Burying the White Gods: New Perspectives on the Conquest of Mexico.' From The American Historical Review, Vol 108, Issue 3. Excerpts, paragraphs 1 - 25.

[3] 'The Great Events of Famous Historians'

[4] Bernardino de Sahagun. 'Florentine Codex: The General History of the Things of New Spain.' Translated by Dibble and Anderson. Sante Fe, 1969. Pages: ?, 42, 168.

[5] Carrasco. 'Quetzalcoatl's Revenge: Primordium and Application in Aztec Religion.' Page 297. History of Religions, Vol 19, No 4 The University of Chicago Press. May, 1980. 'Quetzalcoatl and the Irony of Empire: Myths and Prophecies in the Aztec Tradition, Revised Edition.' Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado. 2000. Pages: 297,150, 308, 298.

[6] Freidel, Schele, Parker. 'Maya Cosmos: Three Thousand Years on the Shaman's Path.' Quill William Morrow. New York. 1993. Pages: 54, 64, 55, 55.

[7] "Quetzalcóatl." Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica Online Academic Edition. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc, 2013. Accessed: 12 Dec. 2013.

[8] Diego de Landa. 'Yucatan: Before and After the Conquest.' Translated by William Gates. Dover Publications. New York, 1978. Pages: ?, 19, 19.

[9] Dalbord-Acton, Ward, Prothero, Leathes. 'The Cambridge Modern History Vol I - The Renaissance.' Page 42. Fourth Edition. The MacMillion Company. New York, 1907.

[10] Collins. 'Cortez & Montezuma.' Harcourt, Brace, and Company. New York. 1955. Page 53.

[11] Byers. The Encyclopedia of World Biographies. Second Edition, Vol 11. Gale Publishing. Detroit. 1998.

[12] Leon-Portilla, Dibble, Edmonson. 'Native Mesoamerican Spirituality: Ancient Myths, Discourses. Stories, Doctrines, Hymns, Poems from the Aztec, Yucatec, Quiche-Maya, and Other Sacred Traditions.' Paulist Press. Toronto, 1980. Pages: II-321, 151, 19, 97.

[13] Colston. 'No Longer Will There Be a Mexico: Omens, Prophesies, and the Conquest of the Aztec Empire. The American Indian Quarterly: Journal of American Indian Studies. Vol IX. Summer, 1985. Page 251.

[14] 'Why Don't Native Americans Have Facial Hair?' http://www.ask.com/question/why-dont-native-americans-have-facial-hair. Accessed December 10, 2013.

[15] http://eatenbyducks.blogspot.com/2010/04/was-quetzalcoatl-viking.html. Accessed: December 11, 2013.

[16] Windsor. 'Narrative and Critical History of America.' Vol I. Mifflin & Company. Boston, 1889.

[17] Hemingway. 'The Bearded White God of Ancient America: The Legend of Quetzalcoatl.' Cedar Fort, 2004.

[18] 'The Letter of Mathetes to Diognetus.' http://fbca.org/files/The-Letter-of-Mathetes-to-Diognetus.pdf. Accessed: December 12, 2013.