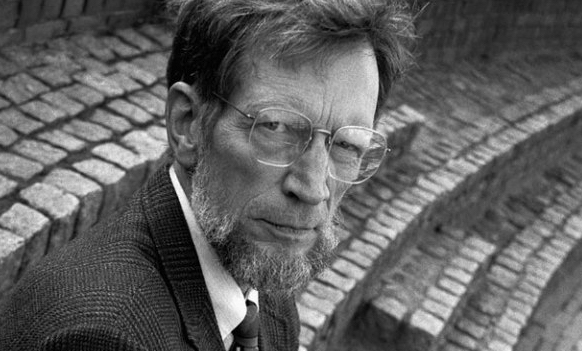

Alvin Plantinga & Christian Epistemology

Alvin Plantinga is among the most important living philosophers, and he's also a Christian. Much of his work involves explaining and justifying Christian faith in the language of analytical philosophy. His primary contributions have been to epistemology (how we know), and his first major work was God and Other Minds in which he compared knowing God with knowing that other people have minds (how do we know we're not interacting with figments of our imagination?).

I recently finished reading Kevin Diller's Theology's Epistemological Dilemma: How Karl Barth and Alvin Plantinga Provide a Unified Response and Plantinga's own short book Knowledge and Christian Belief. Both of these works deal with questions about how Christians can know, especially about God.Diller's book asks how theology can reconcile two seemingly contradictory claims: that theology can speak confidently about spiritual truth and doctrine, and that human theologians are fallen and incapable of attaining uncorrupted knowledge. Diller's solution is to synthesize Karl Barth's claim that all human knowledge about God is divinely gifted via revelation with Plantinga's concept of religious knowledge being known in the "basic way." Knowing in the basic way is similar to the way we recall a memory without having any proof that the memory is an accurate representation of a past event.

Both books are reactions against skepticism and its recent outburst in the New Atheist movement, characterized by figures like Richard Dawkins and Daniel Dennet, but also against the foundations of Enlightenment epistemology defined by ideas like those of Rene Descartes.

Most of what humans actually know is not empirically provable, and if we take skepticism to its logical extreme, demanding the kind of scientific proof that atheists like Dawkins argue we must have, we find that absolutely nothing is provable. Diller reviews some examples of what he calls large-scale epistemological failures like our entire world being a simulation created by the Matrix and our not even being human beings (Zhuangzi's butterfly dream). These large-scale failures seems absurd, and yet they cannot be disproven. There is always a significant chance that almost nothing we believe is true. Diller points out that theology is not the only field to suffer from this epistemological crisis. So far, every field of knowledge has failed to formulate a non-circular foundation for its claims, even the hard sciences have failed in this regard. Theology, however, has suffered more because it often feels like it has failed in a more extensive way.

Plantinga's solution to these problems involves the category of knowing in the "basic way." We all have a sensation of knowing things despite not really being able to prove that our knowledge is really knowledge. We look out over a field and see a sheep in the distance. We "know" a sheep is in the field despite the possibility that the sheep is really a fuzzy dog. We don't really need to prove the sheep is there, we just know it as a kind of sensory response. We "know" what we ate for breakfast despite being unable to prove that the entity we think of as ourselves even existed 10 seconds ago.

Plantinga argues that knowledge of God is like knowing in the basic way. People don't argue their way to God, they don't run experiments, they don't add up probabilities. Most believers simply experience a sensation that God exists. All arguments for God, then, are meant to defeat the "defeaters" that come into our lives and threaten to overturn the basic knowledge we have about God's existence. Plantinga follows Paul's argument that everyone should know about God from his creation and are without excuse if they don't. Paul's claim, interpreted through Plantinga, is that nearly everyone who has functioning noetic equipment has some kind of basic knowledge of God, a sensus divinitatis. This seems to be supported by the fact that every human civilization has assumed the existence of gods.

Humans are fallen, however, so the basic sense of God is not as powerful as it should be. Humans are all damaged, and thus the helpfulness of Barth's assertion that revelation is a purely top down gift. The Holy Spirit has to act on humans to repair their basic sense of God. This is a free gift of God, and while we can work with the Holy Spirit, the initiative is all God's. Plantinga calls his model the "Aquinas/Calvin Model" because he sees in those two thinkers the roots of what he's trying to say.

I really enjoyed these two books, and I felt they were especially helpful in allowing me to see some new aspects of the way I think about God. I've spent a good amount of time arguing with atheists, and I've been accused by them of having no consistent system of thought. One atheist labeled me "the Vatican" for my tendency to synthesize all kinds of random ideas from any source or tradition into new defenses of God and Christianity no matter how badly they seemed to contradict arguments I made in the past. According to Plantinga, this tendency is probably the result of my not believing in God because of any argument, the arguments are just "defeater defeaters" utilized to support a knowledge of God in the basic way. I don't actually believe any of my arguments beyond their possibility of being true and their providing a "way of escape" from a defeater that might derail someone's coming to Jesus. Arguments only serve to clear the path for the basic working of the Holy Spirit and the sensus divinitatus.

Plantinga is worth reading, and his ideas are more nuanced and broad than I've portrayed in this short review. I would encourage anyone who's interested in Christian epistemology to read Knowledge and Christian Belief, it's a short book written in an accessible way. I would especially encourage members of the Church of Christ to look into these issues more. I've noticed a tendency in our own tradition to completely ignore epistemology in favor of what we often label "common sense" interpretations of the world and the Bible; which are usually little more than our parochial cultural experiences. It's past time we started to explore deeper theological questions and perspectives.