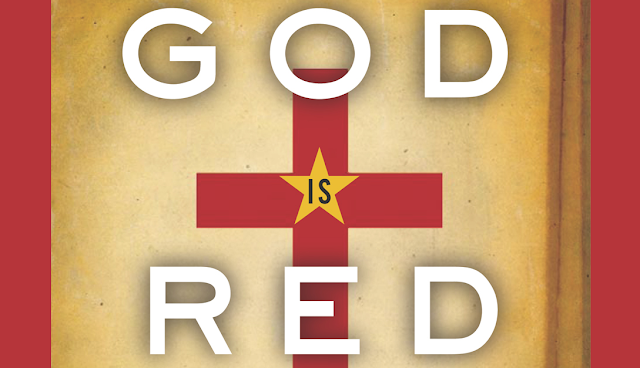

God is Red: The Secret Story of How Christianity Survived & Flourished in Communist China (Book Review)

God is Red was written by Chinese dissident poet Liao Yiwu and published in 2011. It consists of a series of 18 interviews and essays with and about Chinese Christians.

Liao brings his readers into contact with numerous Christians who suffered under Chinese Communist Party (CCP) rule after China's founding in 1949. The stories are often gruesome, but the insights and inspiration are powerful. I teared up numerous times while reading. Liao divides the book into sections based on the region in which they took place, but it might be more helpful to discuss the topic chronologically.

Nestorian Christianity first entered China around AD 700, and then it reentered the region in Western form during the Mongol Empire when Jesuit missionaries entered the imperial court and were employed to teach local scholars (it was through these interactions that Chinese first learned that China was not at the center of a flat earth). Christians also introduced advanced mathematics into China. These facts are not in the book, Liao's chronology starts in the late 1800s with the China Inland Mission led by Hudson Taylor and Catholic missionaries who crossed into southern China via French Indochina (Southeast Asia).

These early missionaries shocked the mostly rural villagers Liao writes about. The first generation of Chinese Christians described foreigners with "yellow and red hair, green eyes, and large crooked noses" who saved thousands during epidemics, taught hygiene, and provided free schooling. Whole regions turned to Jesus.

Among the more striking features of Liao's book are the depictions of extreme material and intellectual poverty in China. There are multiple accounts of people eating bark, grass, and resorting to cannibalism during times of extreme famine. One man said he had never taken a bath until he was over 30 years old. There was almost no idea of basic hygiene before the arrival of missionaries. Superstition dominated people's lives even in the early twentieth century. One man's wife was burned alive after villagers heard a rumor she'd seen a snake that was thought to spread leprosy. Among the missionaries' first jobs upon entering a Chinese village was to explain to the people the various tricks and lies used by shamans to control them.

These early missionaries were true heroes. They rode for days on donkeys into remote villages. They were murdered in some places and faced vicious anti-foreign sentiment and conspiracies. On one occasion, locals spread rumors about missionaries eating orphan children or turning them into pygmies. Nuns were rumored to be vampires. Generally, however, missionaries gained the people's trust through the beneficial services they freely offered.

Christianity spread rapidly in China during the early twentieth century. Most of China's post-Imperial elite reformers were Christians. These prominent figures included Sun Yat-sen, founder of the Republic of China, and Chiang Kai-shek, who led China through World War II and later founded modern Taiwan. Christianity grew swiftly within all social classes under these early Republican Nationalists. The growth came to a grinding halt, however, in 1949 when Mao Zedong's CCP defeated Chiang Kai-shek's Nationalists. China became an officially atheist communist country where religion and traditional culture were violently suppressed. 2,500 years of Chinese civilization came to an end in the subsequent Cultural Revolution, and Christianity was targeted in this purge. Liao's book focuses primarily on these post-1949 persecutions.

Almost all foreign missionaries were forced to leave the country after the CCP conquered China. Many of the book's Christians recount the devastating results of this departure. Whole communities were plunged into desperation by the loss of missionary run medical facilities. One blind man described losing his sight in childhood after running out of the free eye drops his family was receiving from a Catholic priest.

Most Chinese Christians were labeled "landlords" by the Communist Party despite many of them being extremely poor. One seminary student was forced to give up his only blanket after CCP enforcers labeled him a landlord and confiscated his property. These Christians were accused of being anti-revolutionary and opposing the government's new Marxist values.

The Christians interviewed in the book came from many different backgrounds across China, but their experiences of persecution were often similar. Most were accused of spying for "capitalist" and "counterrevolutionary" forces that threatened the Party; most of them endured denunciation meetings in which they were forced to stand in front of thousands of people while being screamed at, humiliated, and forced to confess fake crimes. Many lost family members and friends who were executed for their faith or beaten to death by Red Guards or riotous crowds. The anti-Christian violence went on for decades, and public religious services were effectively impossible between 1955 and 1982.

Despite their churches being destroyed meetings being canceled for thirty years and not being able to speak about their faith, these Chinese Christians preserved their faith through prayer. More than one of the interviewees was thrown in prison for years, forced to sign fake confessions, forced to attend daily indoctrination sessions, and sent to prison labor camps. Through it all, they maintained faith through prayer. Perhaps the worst part of their torture was the suffering they brought upon their families. The wives of persecuted men had to care for large families alone in a heavily patriarchal society. These women were fully dedicated to the Lord and accepted their fate with fortitude. Their children were blacklisted as class enemies and incapable of finishing school or holding public positions in society.

The tortures Christians suffered were intense and long lasting. One man was forced to kneel in the rain with his knees on broken tiles for three days and three nights, he was beaten whenever he began to fall asleep, and he received no food or water. Upon release, he dragged himself home through the mud and clawed at his door until his wife found him half dead. Another man was tortured for years before being publicly executed and having his body dumped in a ditch on the side of the road. The family wasn't allowed to recover it for ten months. His mother tried to drag his corpse out of the muddy ditch and it fell fell apart in her arms.

The book's many descriptions of the Cultural Revolution, and the endless slogan chanting and denunciation meetings, presents a powerful description of every day life in Mao's China. Over and over again, Christians describe the endless slogans and mob brutality as they were spat on and beaten. These denunciation meetings dragged on for more than a decade and became so routine that the victims described memorizing confessions and "arriving on time" when the local CCP needed them as objects for mass abuse. One man commented on how villagers who'd lived together harmoniously their entire lives were suddenly abusing and killing each other for absolutely no reason. The effects of Marxism on China resembled something demonic, a sudden mass hysteria of hatred across an entire nation.

Despite decades of chaos, the really intense persecutions finally ended when Mao died. One man described chuckling when his work commune's loudspeaker declared Mao Zedong had died. The man found it ridiculous that for so long they'd chanted "long live Chairmen Mao" and yet the great demi-god had finally just died like a normal person. The man later converted to Christianity after being disillusioned with the failures of communism.

Deng Xiaoping came to power after Mao's death and began the "reform and opening" movement in 1979. This included a gradual loosening of religious restrictions. Almost immediately, Christianity exploded back to life. Millions of people embraced Jesus after decades of communist inspired chaos and desolation. The Soviet Union began collapsing in 1989 which further discredited the CCP's ruling ideology. Suddenly, in less than a generation, the state ideology and the entirety of socialist society had lost legitimacy. Christianity rushed in to fill the void. Religion revived. Communism was a dead god, and people were looking for a living hope.

Persecution remains in China, however, but at lower levels of intensity. Liao interviewed several Christians who have suffered government abuse since 1979, and several of these interviews were conducted in precarious situations involving police interference. God is Red was published the year before Xi Jinping came to power. In the ten years since, Xi has enforced much stricter controls on religion. In 2020, China was ranked number one in the world for forced church closures and demolitions. Persecution against Christians is now worse than it has ever been in the twenty first century, and it's getting worse.

God is Red is probably as relevant now as it was in 2011, but for different reasons. In 2011, it looked as though Liao might be writing the back story for a triumphant Christianity which had already become China's largest formal religion. Today, Liao's book reads more like a warning of what communist governments are willing to do to protect their legitimacy. We should pray for present members of Chinese church and for the coming day when China becomes a Christian civilization.