Distant Voices: Discovering a Forgotten Past for a Changing Church (Book Review)

C Leonard Allen's 1993 book 'Distant Voices: Discovering a Forgotten Past for a Changing Church' is dedicated to recovering some of the "hidden history" of the Churches of Christ. His aim is to rediscover lost memories so that our tradition can broaden its horizons and dream bigger dreams for the future. He moves chronologically from the beginning of the Restoration Movement to the middle of the twentieth century outlining the oft hidden views and beliefs of some of the Church of Christ's biggest historical names while demonstrating that despite the modern Church of Christ's focus on specific doctrinal boundaries surrounding musical instruments, inter-denominational fellowship, women's participation, and other issues, the Church of Christ has always been a big tent of divergent opinions.

In the first chapter, Allen discusses the relationship between our selective memories of the past and our current narratives about ourselves and our destinies. We think that we remember the past accurately and that our life story grows organically out of events, but research shows this to be simplistic. The mind selectively remembers and forgets based on the needs of our story. A change of direction sometimes occurs when we suddenly remember something that contradicts our established narrative and allows us to imagine new horizons. For Allen, this is what the Church of Christ needs: a remembering of the past that can open up a new future. He hopes to encourage this by unearthing buried components of our tradition.

Chapter 2 is about the Cane Ridge Revival of 1801. The revival was one of the founding events of the Churches of Christ, and yet, as Allen points out, it was absolutely at odds with anything the modern mainline Churches of Christ now accept. The revival was filled with passionate emotional outbursts, faintings in the Spirit, and diverse Lord's Supper practices involving day long feasting. The conservative Presbyterian backlash against this passionate unruly outburst eventually led Barton W Stone to break off and form the Springfield Presbyter which eventually dropped all denominational associations and dedicated itself to pure New Testament Christianity. The modern Churches of Christ were founded in heterodox conditions very similar to those we now label "pentacostal" and condemn as false doctrine. The Church of Christ has become very similar to the denominational conservatives from which we originally rebelled.

Chapter 3 is about Barton Stone's belief that only through the direct work of the Holy Spirit can Christians be united. Stone once believed Christians could unite on the Bible alone, but he lost faith in this idea because sincere believers do not agree on what the Bible taught. The only hope for unity is for each Christian to begin the work of union within themselves and wait for the Holy Spirit's help. Stone condemned the Church of Christ's characteristic tendency to elevate unwritten creeds as standards of unity and fellowship. He said that it's better to have written creeds than unwritten opinions that carry the authority of creeds. In the end, Stone realized that only the direct work of God could enable true union: "O! for a revival of God's own work in the world!"

Chapter 4 is about the early women preachers of the Restoration Movement. Most of them worked in the American Northeast and were associated with the "Smithites." Despite early success, however, women preachers soon disappeared from the movement with the rise of the "true womanhood" ideal of the mid-1800s.

Chapter 5 is an interesting explanation of how the idea of a simple plan of salvation emerged. The characteristic Church of Christ belief that people are saved at baptism emerged as a reaction against what has been called "anxious seat waiting" or the "experiential idea of conversion." It was thought that the Spirit had to move a person in some way before they could be saved. People often spent years in agony waiting for a sign that God had saved them. Only when person had this sign would a congregation allow them to enter their fellowship. One restoration preacher asked a 77 year old man why he'd never become a Christian, and the man responded that he'd been waiting for God to make him a christian. When the preacher explained that he didn't need to wait to obey the man was gladly baptized within the hour. The Church of Christ's message of a simple plan of obedience was good news to many who lived in doubt and anxiety. However, this early restoration reaction against the role of the Holy Spirit in conversion eventually evolved into a deeper reaction against any direct modern work of the Spirit in our lives.

Chapter 6 discusses the doctrinal differences between Barton Stone and Alexander Campbell that persisted after the 1832 union of the Stonites and Campbellites in Lexington. Stone believed it was okay to fellowship with unbaptized Christians because if it was not okay than many great Christians throughout the centuries would have to be disfellowshiped. Although Campbell disagreed, and thought the issue worth fighting over, he too believed the unbaptized could be saved. Stone believed a true Christian was not marked by correct doctrines but by the work of the Spirit in their life. Stone focused on the restoration of spiritual holiness in a person's life, but Campbell focused on the restoration of a particular primitive "order" of the church. Stone objected that Campbell had constructed an unwritten creed while trying to restore this order. Despite their many differences, however, both Stone and Campbell saw each other as Christians and continued working together until death.

Chapter 7 is covers the differences between Stone and Campbell's ideas about how God works in the world. For Stone, God could work directly and personally, and he believed that history would culminate in God's apocalyptic in-breaking into the world. For Campbell, God's modern work was limited to the Bible. Campbell went so far as to say that when we pray we shouldn't even expect people's "impulses" to be changed. He also wrote that "all the power of the Holy Spirit which can operate on the human mind is spent," everything is now worked out according to natural laws and the Bible. Stone disagreed, and he wrote that, according to Campbell's view, "we pray God daily to perform miracles, but in disbelief of them." Campbell thought that man could basically take care of himself and that with the advances of science, technology, and his restored religious order man was gradually going to build a utopia on earth in which Christ would reign. Stone, however, thought this progressive evolution was impossible because man is weak and all historical improvement is accomplished by God's initiative.

Chapter 8 is about Alexander Campbell's later shift in emphasis. Campbell began to fear that his focus on baptism had been reduced to "ammunition" against other denominations, and that the Churches of Christ were becoming controversial and obsessed with "heresy hunting." In 1837, he wrote that there were many saved Christians in the denominational "sects" and he did not believe that a man absolutely had to be baptized in order to be a Christian. Campbell made a subtle distinction, which was lost on his belligerent followers, that faith in Jesus led to the forgiveness of sins but baptism led to the "formal" forgiveness of sins, the two events might not be the same. Physical baptism was the plan of God, but not being baptized out of ignorance was not enough to void a person's salvation. Campbell's apparent reversal inspired a backlash among the lay members of the Church of Christ who'd been fighting the denominations using baptism as a weapon to convince people to defect from these false "sects." Even the most confrontational founders, like Campbell, still held ecumenical views, and they did not believe it impossible to be saved inside a denomination.

Chapter 9 is about Alexander Campbell's medical doctor and fellow Millennial Harbinger editor Dr Robert Richardson. Richardson believed the Restoration Movement had devolved into heartless formalism by emphasizing doctrinal fighting and the passionate denunciation of denominations. He believed Christianity was about the inner work of the Holy Spirit to remake Christians into the image of God. Richardson believed Protestantism has devolved into a a giant factional argument, to the point that people mistook belief in the right doctrines as the meaning of Christianity. He believed this tendency was accelerated by the belief that the Holy Spirit had no prominent role in the modern world. Richardson wrote that the advocate of the "'word alone' view of God's modern work 'amuses himself with the notion that he has resolved all the mysteries of the Holy Spirit.'" Richardson went on to author the greatest personal devotion book ever published in the movement.

Chapter 10 focuses on Robert Richardson's ecumenical views and what he saw as the meaning of the Churches of Christ. "The movement sought to recover a core of essentials comprising a 'common Christianity.'" Christians could unite around this rediscovered core. While most of the movement was moving towards intolerance, to the point of believing that every single differing opinion was actually a failure to understand doctrine, Richardson argued that the formalist wing of the movement had failed to understand the difference between the gospel and the Bible. The apostles did not have Bibles, they only had the gospel message. Richardson believed Christians should unite around the core gospel message while using the Bible as a limiting range of acceptable opinions. He criticized the notion that Christianity was about doctrines: "Christ is not a doctrine, but a person." Christians would never find doctrinal unity, but they already had unity via the indwelling Holy Spirit who was working despite their doctrines.

Chapter 11 is about Richardson's view of salvation and mystery. Christianity is not about doctrines, because salvation rests on the mysterious workings of the Spirit to renovate Christians into a dwelling place for God's Spirit. "True religion means entering into spiritual union with God." By contemplating mystery, not formal doctrines, we draw into closer union and understanding with God.

Chapter 12 is about the Church of Christ's evolution from a largely pacifist movement to a fully mainstream one by the middle of the twentieth century. The movement's original pacifism was expressed in David Lipscomb who argued in a small book, 'Civil Government,' that the church was the adolescent kingdom of God destined to displace all forms of secular government. Secular governments were originally formed in rebellion against God's direct rule, and the church would eventually displace them. Lipscomb believed Christians should not fight in wars, hold political office, or even vote. By World War II, however, his position had practically disappeared and was subsequently condemned as false doctrine. There were even calls to burn all copies of the book.

Chapter 13 and 15 are about the industrial revolution, wealth disparity, and the place of the poor in the church. Lipscomb's view was that the poor represent an elect class chosen for God's work. He viewed the rich as a corrupting influence on the church, and he condemned churches for upgrading their facilities, preachers, and dress codes in ways that made the poor feel as though they weren't really welcome. He said this often happens subconsciously, but when people dress too nicely for church the poor inevitably feel out of place and retreat. Lipscomb viewed the church and the gospel as primarily meant for the poor, and everyone else who entered the church should curve their behavior to conform to the norm of poverty. Many churches at the time were building elaborate church buildings which some thought were a waste of money and scared off the underclass. This conflict had several flash points including the construction of the Central Christian Church in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Chapter 14 is about Lipscomb's, and other's, conviction that there should be no formal offices in the church. The offices of elder and deacon were simply descriptive terms, in his view, that were not vested with any formal authority or power. They believed that the original Greek words did not carry with them the idea of a formal office and that they only referred to age, the titles "elder" and "deacon" merely applied to those who were already filling the roles. Allen presents the modern idea of a board of elders as an import from the rapidly developing corporate structure that was then taking over American business. Lipscomb opposed this import, and he felt that these formal offices would make lay members feel they didn't need to study for themselves or evolve into these formal positions by doing the work assigned to those positions. Individual Christians were under God alone, Lipscomb said, and they could only be led by the wisdom and teaching of elders. Members shouldn't be forced to follow the will of formal office holders.

Chapter 16 is about the role of tradition in Christian life. Early America was a rootless society in which people "arrive in the depth of the wilderness without knowing one another." The prevailing attitude was that God was creating in America the beginnings of a new epoch in human history; American Christians should cut away all traditions and create something new or else return to the original source. This attitude had a large impact on the Restoration Movement and Churches of Christ. Everything before Protestantism was dismissed as heretical "priestcraft." Campbell taught that only when a person read the Bible as though it had fallen out of the sky without any commentary could one come to the knowledge of truth, all formal ideas must be erased from the mind. BA Hinsdale, however, suggested a different relationship with tradition. He wrote: "The tradition of the Church has value... not because it comes through an infallible channel, but because it exhibits a consensus of intelligent interpretation." He argued that, for all its past failures, the historic church had preserved the core elements of Christianity throughout the ages, and it should be respected and consulted.

Chapter 17 is organized around a debate between Silena Holman and David Lipscomb about the role of woman in the church. Holman, an elder's wife and mother of eight, argued that woman had the right to speak in front of the church and preach. She thought it absurd that she was allowed to teach a hundred men one at a time in her living room, but unable to teach a hundred men at one time in front of the church. Lipscomb, however, argued that woman should stay in the home where God intended them, and that if they overstepped their established role the whole moral order would be disrupted.

Chapter 18 is about the place of deaconesses in the church. Many founding members, like Campbell, believed that women must serve as deacons in order for the original order of the church to be reestablished. This position was quiet common in the 1800s, but it had been completely rejected by the turn of the century.

Chapter 19 is about James Harding's conviction that Christians should not save money. He wrote: "If one is righteous, he does not need to lay up treasures for the future; for as the need arises the supply will come. This is as certain as any of the commands of God." Harding blamed people's fear and lack of trust in the Spirit's provision as some of the biggest reasons Christians failed to spread the gospel and build up the church. He said in 1910, after thirty-six years of practice, that he'd striven to follow the directions of Jesus literally, and that he owned no house, no savings, and no property beyond his daily use. We should not accumulate more than what's necessary for our daily use. When some Christians replied that he was ignoring the natural laws by which God provided for us through work, Harding responded that God had natural laws which we did not understand and through which he could provide for us without our seeking that provision out.

Chapter 20 is about TB Larimore's conviction to "finish his course without ever, even for a moment, engaging in partisan strife with anyone about anything." Around the turn of the century, the Churches of Christ were deeply divided about instrumental music, missions cooperatives, and preacher's contracts. Larimore was repeatedly attacked by movement leaders because he refused to take sides in these conflicts. He refused to speak on any of these issues because he viewed them as "untaught questions" not addressed in the Bible. Larimore tried to bring unity to the movement, but ultimately the movement did split into several denominations.

Chapter 21 is about KC Moser's and GC Brewer's stand against what they condemned as "plan theory" preaching. They argued that Churches of Christ had replaced Jesus with a plan as the means of salvation. They fought against the tendency of preacher's to constantly revisit the plan of salvation instead of exploring more deeply the meaning of Jesus' life. Instead of telling people to embrace Jesus, preachers often acted as though sinners just had a duty to follow God's plan. Moser and Brewer believed this made Jesus almost a sidekick of the real source of salvation: the plan. Moser was attacked so much that he developed health problems and had to temporarily retreat from public preaching.

Chapter 22 is the book's conclusion. Allen summarizes the book's purpose as unearthing buried voices and views from the past so that the Church of Christ can hopefully dream bigger dreams and move in a different direction. He believes the Churches of Christ have become locked in an established official history of their purpose and doctrine that leaves no room for exploration or reevaluation. This stagnation has led to decline. By looking to the past, we can perhaps redefine ourselves and find new meaning.

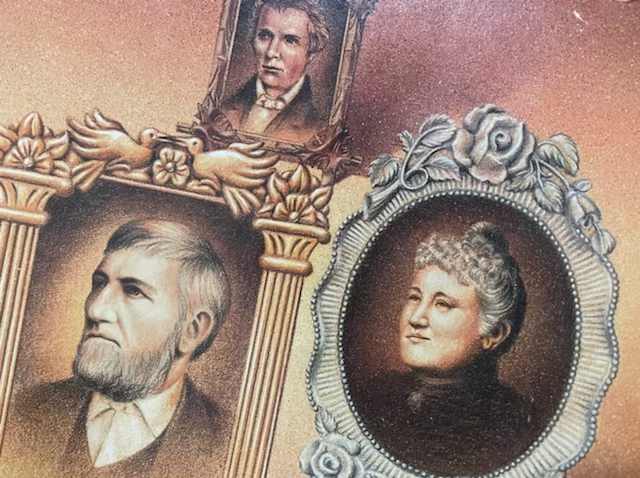

'Distant Voices' is well written and easy to read. It includes several nice pictures. I found the information new and insightful, and it made me think about what the Church of Christ has meant and can mean in the future. However, I doubt the Church of Christ's many hard line heresy hunters will find its message convincing. I can imagine them responding to the book by claiming it was okay for these past men to endorse false doctrine because they were working up towards our present understanding; but, they would argue, if you agree with them now you're going backwards into sin. However, it's been almost three decades since Allen's book was published, and the message seems to have been heeded by a sizable portion of the Churches of Christ. It does feel as though we're increasingly rethinking our mission and expanding our horizons.