Review of Thomas Campbell's 'Declaration & Address'

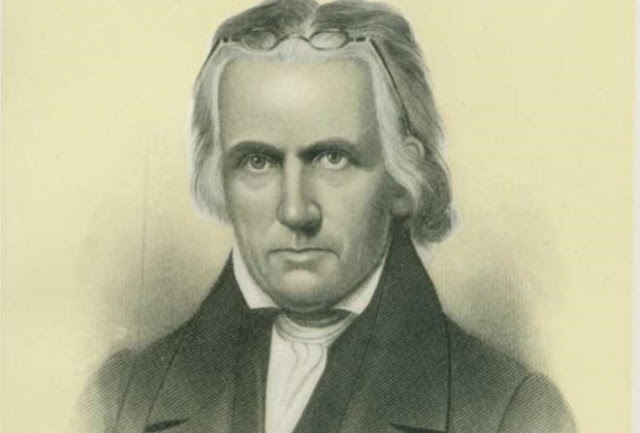

INTRODUCTION. Thomas Campbell's 1809 Declaration & Address of the Christian Association of Washington is one of the modern Church of Christ's two major founding documents (along with Barton W Stone's 1804 Last Will & Testament of the Springfield Presbytery). All modern Churches of Christ, and associated colleges, trace their historical roots back to this document in some way. Church of Christ members were once popularly referred to as "Campbellites," and the Declaration & Address is among the reasons we earned that nickname. Understanding our roots is crucial to understanding our identity. History forms the lens through which we understand ourselves, and the Declaration & Address may be the most important document we have for that kind of self-discovery outside the Bible.

I didn't know what to expect when I first began reading the Declaration & Address. I was torn between imagining it as a straightforward statement of beliefs largely mirroring what I'd been taught growing up or as an obscure document whose meaning had been lost in the intervening centuries. What I discovered was a mix of the two. The seeds of the modern Church of Christ can definitely be found in Campbell's writing, and yet there are central tenets of our fellowship's belief system that are totally divorced from anything he seems to have believed. However, with some cognitive effort it's not difficult to imagine how this evolution occurred over the last several generations.

In this review I'll first cover some of the shocking things the Declaration & Address does not say before covering what it does say. I'll offer a personal critique of the document and suggest some lessons we can take from it as twenty-first century Christians.

WHAT CAMPBELL DID NOT SAY. Shockingly, there's not a single reference to baptism or instrumental music in the entire 27,500 word 66 page document (interestingly, this is also true of Stone's Last Will & Testament). The modern Church of Christ is publicly known almost exclusively through these two issues, and yet this wasn't the case in Campbell's time. His small book contains shockingly few references to doctrine of any kind. There's almost nothing specific about church organization, leadership, women in the assembly, the Holy Spirit, or any of the other issues that have consumed our fellowship over the last several decades. Campbell probably had strong opinions about all these issues, but he didn't seem to think them relevant to his audience.

Campbell did not claim he wanted to restore the true church. The word "restoration" is found only three times in the Declaration & Address, and only one of those references could be construed as something similar to restoring the true church. Campbell preferred the term "reformation" and used it fifteen times. When Campbell wrote of "restoration" he seems to have meant the restoration of specific lost elements of the original church rather than a restoration of the whole church; for example: "the restoration and maintenance of Christian unity." Campbell's use of the term "reformation" is typified in his fifth point of the Declaration:

"That this Society by no means considers itself a Church, nor does at all assume to itself the powers peculiar to such a society; nor do the members, as such, consider themselves as standing connected in that relation... but merely as voluntary advocates for Church reformation; and, as possessing the powers common to all individuals, who may please to associate in a peaceable and orderly manner."

Campbell didn't see himself as restoring a lost church but as operating within an already existing one that had fractured into different pieces and lost its original unity. He regarded himself as a reformer similar to Martin Luther.

Campbell did not claim that denominations were outside the church. He regarded them as broken pieces of the one true church. The Declaration & Address was a plea to fellow Christians of all denominations to reform themselves for the sake of unity: "The cause that we advocate is not our own peculiar cause, nor the cause of any party... it is a common cause, the cause of Christ and our brethren of all denominations." He made numerous similar proclamations throughout the document: "Dearly beloved brethren, why should we deem it a thing incredible that the Church of Christ, in this highly favored country, should resume that original unity, peace, and purity?" He also used the word "evangelical" six times to describe his ideal united church.

Campbell did not connect the restoration of the first century church with personal salvation (as many modern Church of Christ members do). We usually assume a person's salvation comes from being baptized for the "right reasons" and attending a faithful Church of Christ. Campbell didn't make that connection. He assumed the denominations were true churches and their members were true Christians, but he bemoaned the universal church's "sad divisions." Jay Smith expressed his shock at realizing this in his Notes on Thomas Campbell’s Declaration and Address published in the Restoration Quarterly in 1961:

"the difference of our [Church of Christ] stance from that of Thomas Campbell is more fundamental. We have preserved his method, but we have a different objective! This is the discovery that surprised me. It was not what Thomas Campbell said that surprised me, it was his total ignoring of a subject which I had been 'reading into' the document. Restoration is not preached among us primarily for the purpose of uniting the religious world, but as the only valid means of salvation. In other words, we feel that without the Gospel restored to its N.T. purity salvation is impossible. To be sure, we still feel that unity is desirable and would come as a result of a return to N.T. practice by all; but salvation is the real objective; and disunity is preferable to risking salvation…. the Declaration and Address proposes Christian unity on the basis of restored N.T. practice by direct appeal to the N.T. as the only standard of faith and practice. The Disciples [of Christ] have preserved the objective of unity; we the method of restoration. Most Disciples have abandoned restoration as a method and seek unity on the basis of broad religious principles and toleration rather than a resolution of differences. We on the other hand, have salvation as the prime objective of restoration, and unity as secondary and the natural result of a restored oneness of doctrine."

According to Jay Smith's reading, and my own, Campbell didn't see much of a connection between restoring the New Testament Church and an individual's personal salvation. It was perfectly possible to be a saved Christian inside denominationalism. Interestingly, despite bemoaning the church's fracture into denominations, Campbell described his own association as a denomination in the first point of the Declaration.

WHAT CAMPBELL DID SAY. The Declaration & Address is fundamentally about one issue: unity. The word alone appears eighty seven times, and the sentiment is dripping from every page. Campbell believed the entire Bible was about unity:

"That it is the grand design and native tendency of our holy religion to reconcile and unite men to God, and to each other… The whole tenor of that Divine book which contains its institutes, in all its gracious declarations, precepts, ordinances, and holy examples, most expressively and powerfully inculcates this. In so far, then, as this holy unity and unanimity in faith and love is attained."Campbell's very next line bemoans the fact that the church had become horribly divided despite being intended as the primary institution for the spread of unity:

"Impressed with those sentiments, and, at the same time, grievously affected with those sad divisions which have so awfully interfered with the benign and gracious intention of our holy religion, by exciting its professed subjects to bite and devour one another."

Unity was Campbell's objective, and everything else he wrote was a matter of method that was subject to his objective. Campbell wrote that he would embrace any scheme for Christian unity that would achieve the goal: "But if, after all, our brethren can point out a better way to regain and preserve that Christian unity and charity expressly enjoined upon the Church of God, we shall thank them for the discovery, and cheerfully embrace it."

Campbell's method for unity is probably best summarized as Christian minimalism. He looked back at church history's accumulated creeds, traditions, and theological systems and dismissed them as unnecessary causes of division. It's not that Campbell thought they were inherently evil or sinful, in fact, he admitted they could be useful: "we are by no means to be understood as at all wishing to deprive our fellow-Christians of any necessary and possible assistance to understand the Scriptures... for which purpose the Westminster Confession and Catechisms may… prove eminently useful." The problem was that creeds more often caused division over "minor" issues than they encouraged Christian cooperation. Campbell's solution was to bind only what the Bible bound and build fellowship on a kind of core doctrine that everyone could agree upon:"That in order to do this, nothing ought to be inculcated upon Christians as articles of faith; nor required of them as terms of communion, but what is expressly taught and enjoined upon them in the word of God," and: "a permanent Scriptural unity among the Churches, upon the solid basis of universally acknowledged and self-evident truths."

Campbell's Christian minimalism reduced the canon of spiritual texts to the Protestant Bible. All the creeds and catechisms were stripped away, and all that remained was a single ancient volume. This reduction in texts effectively erased church history and attempted to imitate the primitive apostolic church: "Nothing ought to be received into the faith or worship of the Church, or be made a term of communion among Christians, that is not as old as the New Testament," and: "we look forward to that happy event which will forever put an end to our hapless divisions, and restore to the Church its primitive unity, purity, and prosperity."

Campbell foresaw the considerable dispute about how to interpret what the core doctrine was going to be. Some Christians might believe that a certain matter of faith was a communion issue while others might not. He suggested that only what was expressly commanded be regarded as a matter of fellowship: "no man has a right to judge his brother, except in so far as he manifestly violates the express letter of the law." Campbell also included "precedent" as relevant to the church, and in so doing he introduced the first two elements of the Church of Christ's hermeneutic "Command, example." However, Campbell strongly opposed the last third of our modern hermeneutic: "necessary inference." He saw human inference as always fallible and unbindable: "there is a manifest distinction between an express Scripture declaration, and the conclusion or inference which may be deduced from it; and that the former may be clearly understood, even where the latter is but imperfectly if at all perceived." One man's "necessary inference" is another man's wacko theory: "we ought not to reject him because he can not see with our eyes as to matters of human inference, of private judgment."

Campbell's insight about "necessary inference" certainly resonates with me. In almost every Church of Christ theological disagreement I've witnessed at least one party has eventually fallen back on some version of the phrase: "Well, my position is just obvious common sense!" As someone once observed: "Common sense is the collection of prejudices acquired by the age of eighteen." The "obvious" and "necessary" inference is often inadvertently assumed from intellectual blind spots. Appeal to common sense is even listed as its own logical fallacy. A necessary inference is only possible if there is no other reasonable alternative interpretation, and yet how often is that the case? Almost never.

The result of the command/example hermeneutic is patternism. The primitive church constituted a pattern of behavior and belief that should be copied by the modern church. Patternism isn't a necessary inference from scripture. There isn't anything in the New Testament that says the church should imitate the first century church for the remainder of time, but Campbell wasn't trying to make it say that. He believed patternism could save the nineteenth-century church from the divisions tearing it apart. He wrote of unity: "Who would not willingly conform to the original pattern laid down in the New Testament, for this happy purpose?" The objective was unity, the method was command/example, and the hoped for result was unity in the form of patternism.

Among the reasons Campbell resorted to patternism was that he'd lost faith in the theological speculation that had manifested in the form of creeds and catechisms. Ironically, this despair in human logic led him to resort to a form of common sense in which he hoped that mankind could accept the plain meaning of the biblical text as a kind of creed:

"[the meaning of the Bible] must be a way very far remote from logical subtleties and metaphysical speculations, and as such we have taken it up, upon the plainest and most obvious principles of Divine revelation and common sense - the common sense, we mean, of Christians, exercised upon the plainest and most obvious truths and facts divinely recorded for their instruction."

Thomas Campbell was from Ireland, but his faith in the average man and "plain truth" was very American. He believed that all men were more or less equally capable of reading and understanding the Bible: "every man must be aloud to judge for himself." Some of this was probably influenced by the new philosophical liberalism that had emerged out of the pseudo-Enlightenment and John Locke's writings (who was very popular in early America and the Campbellite movement).

CRITIQUE. Throughout the Declaration & Address Thomas Campbell assumed a connection between unity and truth. Many have since commented that this connection is paradoxical. Is it possible to unite Christendom under "truth?" Campbell thought that, on some level, truth was a definite thing humans could agree upon, but I think his assumption was too optimistic. Campbell himself said the Bible portrays humans as fallible, fallen, and wretched. Human logic is clouded by limitation and emotion. Most of the divisions that tore the church apart in its first millennia weren't so much disagreements about truth as misunderstandings about language that led to arguments about truth, and these misunderstandings were created by linguistic and cultural differences. The idea that all humans are able to accept one version of truth ignores the postmodern fact that people of different groups and backgrounds don't perceive the same reality. Everyone's logic is clouded, every conversation is marred by misunderstandings and sub-optimal interpretations of verbal and written ques. This is the nature of humanity's fallen existence. Campbell suggested that the only way for the church to reunite outside of his patternist method was mere forbearance and good-natured compromise. From my perspective, this would remain necessary even if the whole church agreed to move in a patternist direction.

Having critiqued Campbell’s common sense patternism, however, I'll admit that I basically agree with him. On some level, the unity of the church necessitates a kind of Christian minimalism. Where is our point of unity if not the Bible? What do Presbyterians, Baptists, Orthodox, Catholics, and Copts all have in common outside the Bible? Not much. the Bible appears to be among our only tools for reunification.

Among the implications of Campbell's program is the seemingly inevitable erasure of history. If the accumulation of church history over the previous eighteen hundred years was merely "the rubbish of ages," as he put it, then what does history really mean? Why did God say his kingdom would last forever if we had to systematically forget its past at the beginning of the nineteenth century? What are we losing when we imply that our history was a massive mistake that should be unlearned? It's easy to forget from the perspective of 1809 or 2019 that creeds arose to meet a need. They weren't the product of corruptors seeking to usurp the Bible's authority, they were fretted over and carefully composed by church leaders hoping to protect Christian truth in eras when most of the population never owned a Bible and couldn't have read one if they owned it. Almost nobody had a Bible for the vast majority of Christian history. Even well respected theologians like Augustine of Hippo (AD 354 to 430) had to borrow individual Bible books from basilica libraries and didn’t have access to even half the Bible before converting. If you were an illiterate peasant in AD 950 the Bible wasn't necessary for your salvation, it was just a book the priest read aloud during church in a dead language you couldn't understand. It's easy for us living in an era of cell phone apps, mass printing, and universal literacy to lose perspective, and our theology will become warped by our ignorance if we fail to appreciate history.

My greatest concern with Campbell's project is whether it's actually possible to imitate the apostolic church. It might have been easier to ignore the differences between the first century church and the modern church in 1809, but huge amounts of historical information about the primitive era have since become widespread. The discovery of the first century Didache in 1873 complicated our vision of what early Christians practiced and believed. Should we fast every Monday and Wednesday just because the Didache teaches that? Should we baptize the dying by pouring water over their heads three times because the Didache teaches that? Furthermore, is it even possible to restore the apostolic church without having apostolic authority via actual apostles? The first century church didn't have the Bible as a cohesive volume of published authority. The first century church had the common active working of the Holy Spirit in every congregation. The first century church didn’t have church buildings or multiple congregations in one city. When one unpacks the meaning of "restoring the apostolic church" one realizes it isn’t a simple course of action, it's not a matter of just accepting common sense facts and patterning off them. The twentieth century Church of Christ answered these hard questions by asserting the Bible alone was the true authority, but in so doing we convoluted our mission. Is our mission to restore the original church, or is it to reduce our source of doctrinal authority down to a single book? The Pentecostals also seek to restore the first century church by imitating its use of the Holy Spirit. The Catholics claim to be the first century church by virtue of apostolic succession through bishops. Are we truly committed to restoring the first century church, or are we just projecting what we want to believe about how the early church would look in contemporary America?

LESSONS FOR THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY. Among the most serious questions the Declaration & Address raises for the modern Church of Christ is that of borders. Where are the church’s borders? Who is a member of the "one true church," and who isn't? Allegedly, the borders are so broad they include members of all protestant churches (according to arguably the most significant restoration figure). Campbell wrote about who should be regarded as a Christian brother in points eight and nine of the Address:

“having a due measure of Scriptural self-knowledge respecting their lost and perishing condition by nature and practice, and of the way of salvation through Jesus Christ, accompanied with a profession of their faith in and obedience to him, in all things, according to his word, is all that is absolutely necessary to qualify them for admission into his Church. That all that are enabled through grace to make such a profession, and to manifest the reality of it in their tempers and conduct, should consider each other as the precious saints of God, should love each other as brethren…"

Campbell believed that making an intelligent repentance and confession along with living a moral life was enough to qualify one as a Christian. This presents a problem for the modern Church of Christ. For more than a century we've occupied ourselves with defining the path to salvation, and it seems the conclusion we’ve reached is that only those baptized and worshiping inside a Church of Christ are saved. This is a neat border, but is it sustainable? It's becoming increasingly important to explore the meaning of "Christian" as the Church of Christ demographically collapses and continues dividing along multiple fault lines. If one of our founding fathers took such a broad interpretation of "Christian" then we should ask ourselves how exclusivist we can be. We often say that unfaithful "liberal" congregations are those that fellowship denominational or "unscriptural" people and groups, but what if the "liberals" are conserving the original restoration principles? What if it's the "conservatives" who are the true innovators deviating from the original purpose?

Another hard question for the modern Church of Christ is whether we've totally inverted Thomas Campbell's original dream? Campbell desperately wanted to restore the church's unity, and he adamantly rejected the idea of creating another "party." The Declaration & Address was meant to heal the division, and yet the churches claiming descent from that heritage are now regarded as among the most divisive groups in Christianity. As far as I can tell, the ecumenical goal has been totally abandoned among the conservative Churches of Christ. Unity has devolved into just another way to condemn denominations: "The denominations are false churches because they refuse to unite with us!" When I lived in the South I'd often hear people say things like: "Oh, you’re Church of Christ? Don't y'all think you're the only ones going to heaven because you don't use instruments?" It’s gotten to the point where we’re recognized almost exclusively for being divisive.

CONCLUSION. Thomas Campbell's Declaration & Address is arguably the most important document ever published in our fellowship. It lays out the movement's vision of ecumenical unity through biblical minimalism. While the conservative Churches of Christ have carried on developing Campbell's patternist method, we've completely abandoned Campbell's primary goal of uniting the Christian world. Thomas Campbell repeatedly asserted that the church would inevitably unite, and that this unity would come regardless of whether the church adopted his method. The modern Churches of Christ have resisted unity by erecting ever higher walls between ourselves and the outside religious world, but the walls are falling anyway. Christians everywhere are uniting across denominational lines as our broader societies are losing religion altogether and descending into nihilism. As biblical knowledge declines, morality collapses, and churches bleed members, younger Christians of all traditions are increasingly realizing they have more in common with each other than with the secular world. Thomas Campbell foresaw our coming unity, but he hoped it wouldn't have to happen this way.